Introduction to OCaml Programming

- We will be using the OCaml language for implementing interpreters, typecheckers and the like

- It is a functional programming language which of interest in its own right

- You are not going to learn how to be an OCaml software engineer in this class however, we are just going to cover the minimal OCaml needed for these tasks

- Take Functional Programming in Software Engineering for a focus on software engineering in OCaml

- OCaml itself has a very minimal set of features which can build up other features, we will also follow that in our toy langauges Fb, FbV, FbR, etc.

What is OCaml?

- OCaml is a strongly typed functional programming language

- Strongly typed means the compiler will detect type errors; you won’t get them at runtime like in JavaScript/Python

- Functional means an emphasis on functions as a key building block and use of functions as data (functions that themselves can take functions as arguments and return functions as results)

- We will also take an emphasis on functions in our study of PLs as functions are more fundamental than e.g. objects/classes.

The top loop

- We will begin exploration of OCaml in the interactive top loop

- A top loop is also called a read-eval-print loop or the console window for other languages; it also works like a terminal shell

- To install the top loop we are using,

utop, follow the course OCaml install instructions. - To run it, just type

utopinto a terminal window.

Simple integer operations in the top loop

(Note if you want to get all the code (only) of this webpage in a .ml file to load into your editor, download the file lecture.ml.)

3 + 4;; (* ";;" denotes end of input, somewhat archaic. *)

let x = 3 + 4;; (* give the value a name via let keyword. *)

let y = x + 5;; (* can use x now *)

let z = x + 5 in z - 1;; (* let .. in defines a local variable z *)

Boolean operations

let b = true;;

b && false;;

true || false;;

1 = 2;; (* = not == for equality comparison - ! *)

1 <> 2;; (* <> not != for not equal *)

Other basic data – see documentation for details

4.5;; (* floats *)

4.5 +. 4.3;; (* operations are +. etc not just + which is for ints only *)

30980314323422L;; (* 64-bit integers *)

'c';; (* characters *)

"and of course strings";;

Simple functions on integers

To declare a function squared with x its one parameter. return is implicit.

let squared x = x * x;;

squared 4;; (* to call a function -- separate arguments with S P A C E S *)

- OCaml has no

returnstatement; value of the whole body-expression is what gets returned - Type is automatically inferred and printed as domain

->range - OCaml functions in fact always take only one argument - ! multiple arguments can be encoded (later)

Everything in OCaml returns values (i.e. is an ‘expression’) - no commands

if (x = 3) then (5 + 35) else 6;; (* ((x==3)?5:6)+1 in C *)

(if (x = 3) then 5 else 6) * 2;;

(* (if (x = 3) then 5.4 else 6) * 2;; *) (* type errors: two branches of if must have same type *)

Fibonacci series example - 0 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 ...

Let’s write a well-known function with recursion and if-then-else syntax

let rec fib n = (* the "rec" keyword needs to be added to allow recursion *)

if n <= 0 then 0

else if n = 1 then 1

else fib (n - 1) + fib (n - 2);; (* notice again everything is an expression, no "return" *)

fib 10;; (* get the 10th Fibonacci number *)

Anonymous functions aka “functions are just other values”

- Key advantage of FP: functions are just expressions; put them in variables, pass and return from other functions, etc.

- There is major power to this, which is why Java, Python, C++, etc have had higher-order functions added to them.

let add1 x = x + 1;; (* a normal add1 definition *)

let anon_add1 = (function x -> x + 1);; (* equivalent anonymous version; "x" is argument here *)

let anon_add1_fun = (fun x -> x + 1);; (* `function` can usually be shortened to `fun` *)

add1 3;;

(add1 4) * 7;; (* note this is the same as add1 4 * 7 - application "binds tightest" *)

((fun x -> x + 1) 4) * 7;; (* can inline anonymous function; useless here but useful later *)

OCaml Lecture II

- Multiple argument functions - just leave s p a c e s between multiple arguments in both definitions and uses

let add x y = x + y;;

add 3 4;;

(add 3) 4;; (* same meaning as previous application -- two applications, " " associates LEFT *)

let add3 = add 3;; (* No need to give all arguments at once! Type of add is int -> (int -> int) - "CURRIED" *)

add3 4;;

add3 20;;

(+) 3 4;; (* Putting () around any infix operator turns it into a 2-argument function: `(+)` is same as our `add` above *)

Conclusion: add is a function taking an integer, and returning a function which takes ints to ints.

So, add is in fact a higher-order function: it returns a function as result.

Observe int -> int -> int is parenthesized as int -> (int -> int) – unusual right associativity

Be careful on operator precedence with this goofy way that function application doesn’t need parens!

add3 (3 * 2);;

add3 3 * 2;; (* NOT the previous - this is the same as (add3 3) * 2 - application binds tighter than `*` *)

add3 @@ 3 * 2;; (* LIKE the original - @@ is like the " " for application but binds LOOSER than other ops *)

Declaring types in OCaml

- While OCaml infers types for you it is often good practice to add those types to your functions, e.g.

let add (x : int) (y : int) : int = x + y;; - Note that the parentheses are required, and the return type is at the end.

- For the homeworks we will give you the types to make clear what the requirements are for the function.

Simple Structured Data Types: Option and Result

- Before getting into “bigger” data types and how to declare our own, let’s use one of the simplest structured data types, the built-in

optiontype. - It is used when either we have some data, or we have nothing.

- In standard PLs there is a

nilorNullorNULLpointer which represents absence of data;optionis a more precise version of those.

Some 5;;

(* - : int option = Some 5 *)

- all this does is “wrap” the 5 in the

Sometag - Along with

Some-thing 5, there can also beNone-thing, nothing:

None;;

(* - : 'a option = None *)

- Notice these are both in the

optiontype .. either you haveSomedata or you haveNone. - These kinds of types with the capital-letter-named tags are called variants in OCaml; each tag wraps a different variant.

- The

optiontype is very useful; here is a simple example.

# let nice_div m n = if n = 0 then None else Some (m / n);;

val nice_div : int -> int -> int option = <fun>

# nice_div 10 0;;

- : int option = None

# nice_div 10 2;;

- : int option = Some 5

There is a downside with this though, you can’t just use nice_div like /:

# (nice_div 5 2) + 7;;

Line 1, characters 0-14:

Error: This expression has type int option

but an expression was expected of type int

- This type error means the

+lhs should be typeintbut is aSomevalue which is not anint. optiontypes are not coercable to integers (or any other type).

Here is another failed attempt which shows how None is not like nil/Null/NULL:

# let not_nice_div m n = if n = 0 then None else m / n;;

Line 1, characters 47-52:

Error: This expression has type int but an expression was expected of type

'a option

- The

thenandelsebranches must return the same type, here they do not. - The

intandint optiontypes have no overlap of members!

Pattern matching first example

Here is a real solution to how elements of option types can be used:

# match (nice_div 5 2) with

| Some i -> i + 7 (* i is bound to what the Some wraps, 2 here *)

| None -> failwith "This should never happen, we divided by 2";;

- : int = 9

- This shows how OCaml lets us destruct option values, via the

matchsyntax. matchis similar toswitchin C/Java/.. but is much more flexible in OCaml- The LHS in OCaml can be a general pattern which binds variables (the

ihere), etc - Note that we turned

Noneinto a runtime exception viafailwith.

One other way to deal with this division by zero issue is the function could itself raise an exception:

let div_exn m n = if n = 0 then failwith "divide by zero is bad!" else m / n;;

div_exn 3 4;;

- This has the property of not needing a match on the result.

- Note that the built-in

/also raises an exception, it more or less is doing what this example does. - Exceptions are side effects though, we want to minimize their usage to avoid error-at-a-distance.

- The above examples show how exceptional conditions can either be handled via

- exceptions (the most common way, e.g. how Java deals with division by 0)

- with Some/None in the return value; the latter is the C philosophy, C functions return

NULLor-1if fail and the caller has to deal.

Lists

- Lists are pervasive in OCaml

- They are immutable (cannot update elements in an existing list) so while they look something like arrays or vectors they are not

- Isn’t it totally impossible to write useful programs with lists that we can’t change?? Surprisingly, its not hard at all.

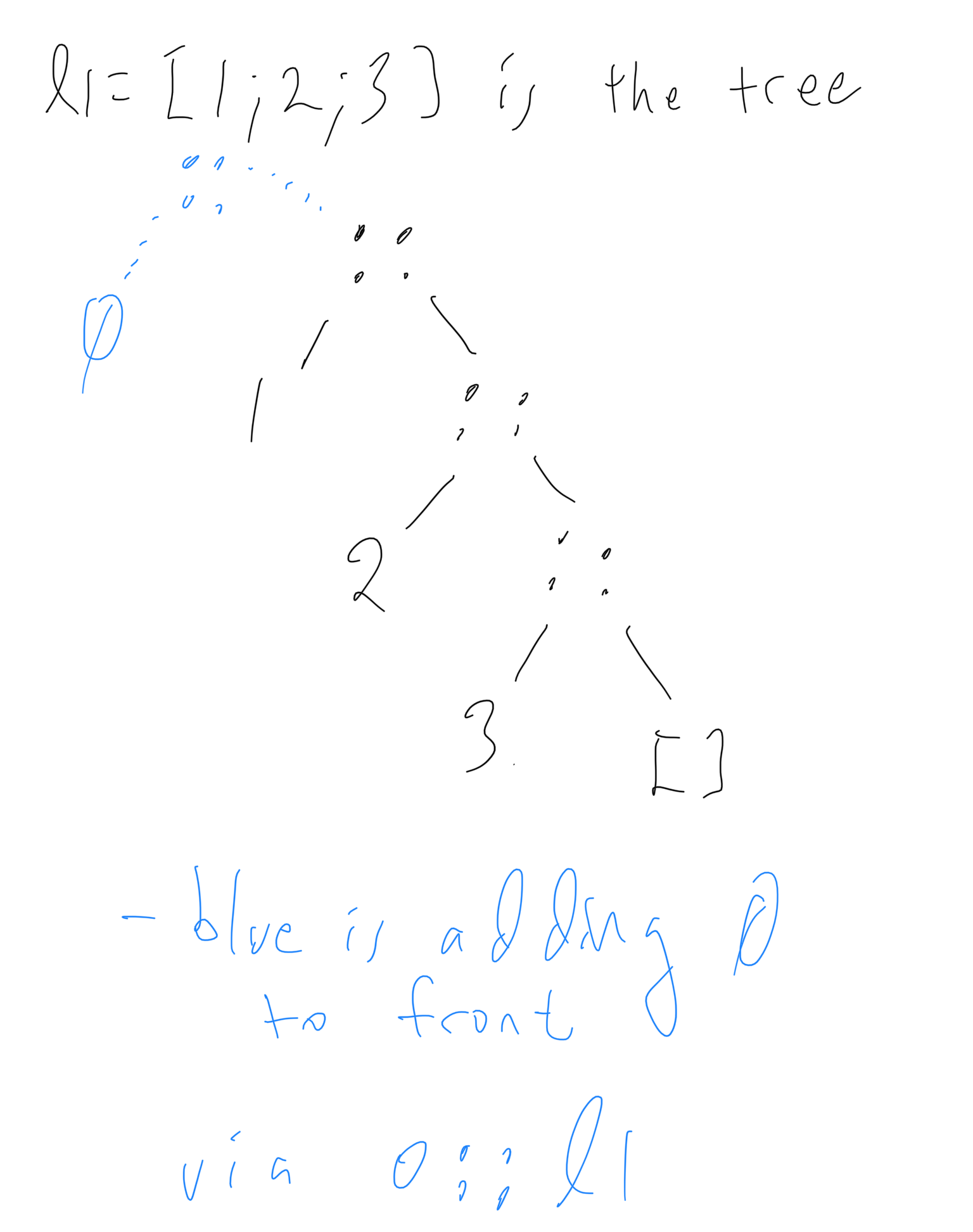

let l1 = [1; 2; 3];;

let l2 = [1; 1+1; 1+1+1];;

let l3 = ["a"; "b"; "c"];;

(* let l4 = [1; "a"];; *) (* error - All elements must have same type *)

let l5 = [];; (* empty list *)

Operations on lists.

- Lists are represented internally as binary trees where the left children are all leaves.

- The tree nodes are

::and are called conses (an historical term from Lisp) - The list is then the list of these left children going down the tree.

::is also an operation to build a new list by adding one element to the front of an existing list- Since lists don’t mutate, sub-lists can be shared (!)

3 :: [] (* also written [3], a singleton list -- tree with root ::, left sub tree 3, right sub tree empty list *)

let l1 = 1 :: (2 :: (3 :: []));; (* equivalent to [1;2;3] *)

let l0 = 0 :: l1;; (* fast, just makes one new node, left is 0 right is l1 - l1 is shared with l0 *)

l1;; (* Notice that l1 did not change even though we put a 0 on - immutable always! *)

[1; 2; 3] @ [4; 5];; (* appending lists - slower, needs to cons 3 then 2 then 1 on front of [4;5] *)

Picture of l1 and l0:

Destructing Lists with pattern matching

- You are used to using

.(dot) to project out fields of data structures; in OCaml we instead pattern match nearly all the time - Here is a simple example of pattern matching on a list to get the head, the first element.

let hd l =

match l with

| [] -> None

| hd :: tl -> Some x (* the pattern hd :: tl binds hd to the first elt, tl to ALL the others *)

;;

hd [1;2;3];; (* [1;2;3] is 1 :: [2;3] So the head is 1. *)

hd [1];; (* [1] is 1 :: [] So the head is 1. *)

hd [];;

Append

- Here is how list append is implemented, recurse on the first list (only):

let rec append l1 l2 = match l1 with | [] -> l2 | hd :: tl -> hd :: (append tl l2) (* assume function works for shorter lists like tl *) ;; append [1;2;3] [4;5];; (* Recall `[1;2;3]` is `1 :: [2;3]` so in first call hd is 1, tl is [2;3] *) 1 :: (append [2;3] [4;5]);; (* This is what the first recursive call is performing *) - Pattern priority: pick the first matched clause

- The above two patterns are mutually exclusive so order is in fact irrelevant here

Applying a function to all list members

- Let us hint a bit at the power of higher-order functions with one example,

keep. - We will pass in a function as a parameter to

keep - The function we pass in returns

true/falseand we keep only the list elements it istruefor - (such a

true/false-valued function is called a predicate in logic) - This example starts to show why anonymous functions are so useful

let rec keep (l : 'a list) (p : 'a -> bool) : 'a list =

match l with

| [] -> [] (* no elements to check p on *)

| hd :: tl -> if p hd then hd :: keep tl p else keep tl p

;;

keep [33;-22;11] (fun n -> n > 0);; (* keep only the elements greater than 0 *)

keep ["hello";"this";"is";"";"fun";""] (fun s -> s <> "");; (* keep non-empty strings *)

Don’t use non-exhaustive pattern matches! You will get a warning (and an error in compiler):

let dumb l = match l with

| x :: y -> x;;

dumb [1;2;3];; (* this works to return head of list but.. *)

(* dumb [];; *) (* runtime error here *)

Built-in List.hd is the same as dumb and it is often a dumb function, don’t use it unless it is 100% obvious that the list is not empty.

List library functions

Fortunately many common list operations are in the List module in the standard library:

List.nth [1;2;3] 2;;

(* - : int = 3 *)

- We will discuss modules later, but for now just think of them as containers of a collection of functions types etc. Something like a

packagein Java, or a Javaclasswith onlystaticmethods.

Some more handy List library functions

List.length ["d";"ss";"qwqw"];;

List.concat [[1;2];[22;33];[444;5555]];;

List.append [1;2] [3;4];;

[1;2] @ [3;4];; (* Use this equivalent infix syntax for append *)

- Type

#show List;;into utop to get a dump of all the functions inList. - NOTE: for assignment 1 you cannot use these

List.functions, we want you to practice using recursion (you can use them after Assignment 1). - The Standard Library Reference page for lists contains descriptions as well.

- There are similar modes for

Int,String,Float, etc modules which similarly contain handy functions.

The Types of List Library Functions

- The types of the functions are additional hints as to their purpose, get used to reading them

- Much of the time when you mis-use a function you will get a type error

'a listetc is a polymorphic aka generic type,'acan be any type. more later on thatList.length;; (* - : 'a list -> int = <fun> *) List.concat;; (* - : 'a list list -> 'a list = <fun> *) List.append;; (* - : 'a list -> 'a list -> 'a list = <fun> *)

Correctness of recursive Functions

Consider list reverse (no need to code as it is List.rev; this is just an example):

let rec rev l =

match l with

| [] -> []

| hd :: tl -> rev tl @ [hd] (* Assume by induction that rev tl "works" since its a shorter list. *)

;;

rev [1;2;3];; (* recall [1;2;3] is equivalent to 1 :: [2;3] *)

Let us argue why this works.

We assume we have a notion of “program fragments behaving the same”, ~=.

- e.g.

1 + 2 ~= 3,1 :: [] ~= [1], etc. - (

~=is called “operational equivalence”, we will define it later in the course)

Before doing the general case, here are some equivalences we can see from the above program run

(by running it in our heads):

rev [1;2;3]

~= rev (1 :: [2;3]) (by the meaning of the [...] list syntax)

~= (rev [2;3]) @ [1] (the second pattern is matched: hd is 1, tl is [2;3] and run the match body)

.. assuming it "works" for smaller lists, we have

~= [3;2] @ 1

~= [3;2;1]

We now want to generalize this to any list, not just [1;2;3]: use induction to prove it.

Let P(n) mean “for any list l of length n, rev l ~= its reverse”.

Tangent: review of why induction works

Recall an induction principle:

To show P(n) for all in, it suffices to show

1) P(0), and

2) P(k-1) holds implies P(k) holds for any natural number k>0.

- Why does this work??

- Think of induction step 2) as a proof macro with k a parameter

- Since it holds for any k, we can plug in any particular number into the macro

- plug in k=1: P(0) implies P(1) has to hold

- plug k=2: P(1) implies P(2) has to hold

- …

So, if we showed 1) and 2) above,

- P(0) is true by 1)

- P(1) is true because letting k=1 in 2) we have P(0) implies P(1),

and we just showed we have P(0), so we also have P(1). - P(2) is true because letting k=2 in 2) we have P(1) implies P(2),

and we just showed we have P(1), so we also have P(2). - P(3) is true because letting k=3 in 2) we have P(2) implies P(3),

and we just showed we have P(2), so we also have P(3). - … etc for all k

Let us now prove reverse reverses, by induction.

Theorem: For any list l of length n, rev l ~= the reverse of l .

Proof. Proceed by induction to show this property for any n.

1) for n = 0, l ~= [] since that is the only 0-length list.

rev [] ~= [] which is [] reversed, check!

2) Assume for any (k-1)-length list l that rev l ~= l reversed.

Show for any k length list, i.e. for any list x :: l

that rev (x :: l) ~= (x :: l) reversed:

OK, by computing, rev (x :: l) ~= rev l @ [x].

Now by the induction hypothesis, rev l is l reversed.

So, since (l reversed) @ [x] reverses the whole list x :: l,

rev (x :: l) ~= (x :: l) reversed.

This completes the induction step.

QED.

OCaml Lecture III

Tuples

- Think of tuples as fixed length lists, where the types of each element can differ, unlike lists

- A 2-tuple is a pair, a 3-tuple is a triple.

- Tuples are “and” data structures: this and this and this.

structand objects are also “and” structures (variants likeSome/Noneare OCaml’s “or” structures, more later on them)

(2, "hi");; (* type is int * string -- '*' is like "x" of set theory, a product *)

let tuple = (2, "hi");; (* tuple elements separated by commas, list elements by semicolon *)

(1,1.1,'c',"cc");;

Tuple pattern matching

let tuple = (2, "hi", 1.2);;

match tuple with

| (f, s, th) -> s;;

(* shorthand for the above - only one pattern, can use let syntax *)

let (f, s, th) = tuple in s;;

(* Parens around tuple not always needed *)

let i,b,f = 4, true, 4.4;;

(* Pattern matching on a pair allows parallel pattern matching *)

let rec eq_lists l1 l2 = (* note `l1 = l2` in OCaml will work so no need to actually write this .. *)

match l1,l2 with

| [], [] -> true

| hd :: tl, hd' :: tl' -> if hd <> hd' then false else eq_lists tl tl'

| _ -> false (* _ is a catch-all pattern; lengths must differ if this case is hit *)

Consequences of immutable variable declarations on the top loop

- All variable declarations in OCaml are immutable – value will never change

- Helps in reasoning about programs, we know the variable’s value is fixed

- But can be confusing when shadowing (re-definition) happens

Consider the following sequence of inputs into the top loop:

let y = 3;;

let x = 5;;

let f z = x + z;;

let x = y;; (* this is a shadowing re-definition, not an assignment! *)

f y;; (* 3 + 3 or 5 + 3 - ?? Answer: the latter since x WAS 5 at point of f def'n. *)

- To understand the above, realize that the top loop is conceptually an open-ended series of let-ins which never close:

(let y = 3 in

( let x = 5 in

( let f z = x + z in

( let x = y in (* this is a shadowing re-definition of x, NOT an assignment *)

(f y)

)

)

)

)

;;

The above might make more sense if you consider similar-in-spirit C pseudo-code:

{ int y = 3;

{ int x = 5;

{ int (int) f = z -> return(x + z); // imagining higher-order functions in C

{ int x = y; (* shadows previous x in C *)

return(f(y));

}}}})

Function definitions are similar, you can’t mutate an existing definition, only shadow it.

let f x = x + 1;;

let g x = f (f x);;

(* lets "change" f, say we made an error in its definition above *)

let f x = if x <= 0 then 0 else x + 1;;

g (-5);; (* g still refers to the initial f - !! *)

let g x = f (f x);; (* FIX g to refer to new f: resubmit (identical) g code *)

g (-5);; (* sees new f now *)

- Moral: re-load all dependent functions if you change any function

- For programming assignments, if you want to play with your code you can copy/paste stuff into the top loop to test, but beware that functions depending on the function you changed may not change

- To be safe, save

assignment.ml, quitutop, typedune utopagain which will compile and load all your code. You will need to typeopen Assignment;;intoutoponce it is going so all your functions are available. - Note you can alternatively type into

utopthe command#use "src/assignment.ml"and it is as if you copy/pasted the whole file intoutop. - Run

dune testto check your overall progress to see which tests pass.

Moral: there are many ways to develop in OCaml, experiment with these different modes to see which is working best for you.

Mutually recursive functions

- Mutually recursive functions require special syntax in OCaml

- Warm up: write a copy function on lists

- List copy is in fact 100% useless in OCaml because lists are immutable - variables can share a single copy without any issues

- This property is called referential transparency

let rec copy l =

match l with

| [] -> []

| hd :: tl -> hd::(copy tl);;

let result = copy [1;2;3;4;5;6;7;8;9;10]

- Argue by induction that this will copy:

(copy tl)is a call on a shorter list so can assume is correct

Now lets do some mutual recursion. Copy every other element, defined by mutual recursion via and syntax

let rec copy_odd l = match l with

| [] -> []

| hd :: tl -> hd :: (copy_even tl) (* keep the head in this case *)

and (* new keyword for declaring mutually recursive functions *)

copy_even l = match l with

| [] -> []

| hd :: tl -> copy_odd tl;; (* throw away the head in this case *)

copy_odd [1;2;3;4;5;6;7;8;9;10];;

copy_even [1;2;3;4;5;6;7;8;9;10];;

Using let .. in to define local functions

- If functions are only used locally within one function, it can be defined inside that function - more modular

- Suppose we only wanted to use

copy_odd: here is a version that hidescopy_even:

let copy_odd ll =

let rec copy_odd_local l = match l with

| [] -> []

| hd :: tl -> hd::(copy_even_local tl)

and

copy_even_local l = match l with

| [] -> []

| hd :: tl -> copy_odd_local tl

in

copy_odd_local ll;;

assert(copy_odd [1;2;3;4;5;6;7;8;9;10] = [1;3;5;7;9]);;

copy_even_localis not available in the top loop, it is local tocopy_oddfunction only, just like local variables but its a function.- Note how the last line “exports” the internal

copy_odd_localby forwarding thellparameter to it - In general if you need an auxiliary function for one of the homework questions, you can either define it at the top level

let aux n = n + 1 (* super simple example auxiliary function *) let solution i = ... aux (i*i) ...or make it purely local:

let solution i = let aux n = n+1 in ... aux (i*i) ...

Higher Order Functions

Higher order functions are functions that either

- take other functions as arguments

- or return functions as results (which we already saw with multi-arg functions)

Why?

- “pluggable” programming by passing in and out chunks of code

- greatly increases reusability of code since any varying code can be pulled out as a function to pass in

- We alreayd saw Curried functions such as

add : int -> (int -> int)which return functions - Also

keep : 'a list -> ('a -> bool) -> 'a listabove let us plug in a predicate (function) - Lets show more power by generalizing an algorithm to extract code we can then plug in

Example: append "gobble" to each word in a list of strings

let rec append_gobble l =

match l with

| [] -> []

| hd::tl -> (hd ^ "-gobble") :: append_gobble tl;;

append_gobble ["have";"a";"good";"day"];;

("have" ^"gobble") :: ("a"^"gobble") :: append_gobble ["good";"day"];;

- At a high level, the common pattern is “apply a function to every list element and make a list of the results”

- So, lets pull out the “append gobble” action as a function parameter so it will be it code we can plug in

- The resulting function is called

map(note it is built-in asList.map):let rec map (f : 'a -> 'b) (l : 'a list) : 'b list = (* function f is an argument here *) match l with | [] -> [] | hd::tl -> (f hd) :: map f tl;;

let another_append_gobble = map (fun s -> s ^ "-gobble");; (* give only the first argument -- Currying *)

another_append_gobble ["have";"a";"good";"day"];;

map (fun s -> s^"-gobble") ["have";"a";"good";"day"];; (* don't have to name the intermediate application *)

Mapping on lists of pairs - in and out lists can be different types.

map (fun (x,y) -> x + y) [(1,2);(3,4)];;

let flist = map (fun x -> (fun y -> x + y)) [1;2;4] ;; (* make a list of functions - why not? *)

- This aligns with the type of

map,('a -> 'b) -> 'a list -> 'b list-'aand'bcan differ.

Solving some simple problems

Here are some practice problems and their solutions for your own self-study (may skip in lecture depending on time available)

Also see the OCaml page examples for more sources for example problems and solutions.

- Write a function

to_upper_casewhich takes a list (l) of characters and returns a list which has the same characters as l, but capitalized (if not already).

Notes:

a. Assume that the capital of characters other than alphabets

(A - Z or a - z), are the characters themselves e.g.

character corresponding capital character

a A

z Z

A A

1 1

% %

b. You can only use Char.code and Char.chr library functions. You cannot use Char.uppercase.

Answer:

let to_upper_char c =

let c_code = Char.code c in

if c_code >= 97 && c_code <= 122 then Char.chr (c_code - 32)

else c;;

let rec to_upper_case l =

match l with

| [] -> []

| c :: cs -> to_upper_char c :: to_upper_case cs

;;

Test

assert(to_upper_case ['a'; 'q'; 'B'; 'Z'; ';'; '!'] = ['A'; 'Q'; 'B'; 'Z'; ';'; '!']);;

Could have used map instead (note map is built in as List.map):

let to_upper_case l = List.map to_upper_char l ;;

Could have also defined it even more simply - partly apply the Curried map:

let to_upper_case = List.map to_upper_char ;;

- Write a function

partitionwhich takes a predicate (p) and a list (l) as arguments and returns a tuple(l1, l2)such thatl1is the list of all the elements oflthat satisfy the predicate p and l2 is the list of all the elements oflthat do NOT satisfyp. The order of the elements in the input list (l) should be preserved.

Note: A predicate is any function which returns a boolean. e.g. let is_positive n = (n > 0);;

Answer:

let rec partition p l =

match l with

|[] -> ([],[])

| hd :: tl ->

let (posl,negl) = partition p tl in

if (p hd) then (hd :: posl,negl)

else (posl,hd::negl);;

Test

let is_positive n = n > 0 in

assert(partition is_positive [1; -1; 2; -2; 3; -3] = ([1; 2; 3], [-1; -2; -3]))

- Write a function

diffwhich takes in two lists l1 and l2 and returns a list containing all elements in l1 not in l2.

Note: You will need to write another function contains x l which checks whether an element x is contained in a list l or not.

Answer:

let rec contains x l =

match l with

| [] -> false

| y :: ys -> x = y || contains x ys

;;

let rec diff l1 l2 =

match l1 with

| [] -> []

| hd :: tl ->

if contains hd l2 then diff tl l2

else hd :: diff tl l2

;;

Tests

assert(contains 1 [1; 2; 3]);;

assert(not(contains 5 [1; 2; 3]));;

assert(diff [1;2;3] [3;4;5] = [1; 2]);;

assert(diff [1;2] [1;2;3] = []);;

All of the above functions can simply pass the tail of the list in the recursion. Sometimes you need to pass additional information down the recursion to accumulate something. For example lets write a list_max function which returns the maximal integer in a list. Note that the list could be empty, we will return Int.min_int in this case, the smallest integer.

let rec list_max_aux n l = (* invariant: n is the maximal integer seen thus far *)

match l with

| [] -> n

| hd :: tl -> if hd > n then list_max_aux hd tl else list_max_aux n tl

let list_max = list_max_aux Int.min_int (* prime the pump *)

OCaml Lecture IV

- There is a better way to program over lists than to use

let rec, it is called combinator programming - use the library functions - We already saw this with

map- we didn’t need to writeappend_gobbledirectly, instead we could usemap.Folds

fold_left/fold_rightuse a binary function to combine list elements- Think of

folding as something you feed just the “base case code” and the “recursive case code” to for a function on lists, and it builds a recursive function for you. - As with

maplet us first write a concrete combiner and then pull out the particular combination code as a parameter

let rec char_list_to_string l =

match l with

| [] -> "" (* "" is the "base case code" we will want to plug in later *)

| elt :: elts -> (* we are calling the current list element `elt`, thats the convention in folding *)

let accum = char_list_to_string elts in (* this is what `accum` is, the *accumulation* from recursing *)

(Char.escaped elt)^accum;; (* this is the "recursive case" code: put elt on front of result thus far *)

char_list_to_string ['h';'e';'l';'l';'o';'!'];;

Let us make a minor tweak to this to make clear that the recursive case code can be pulled out as a function:

let rec char_list_to_string l =

match l with

| [] -> ""

| elt :: elts ->

let accum = char_list_to_string elts in

let f = fun elt accum -> (Char.escaped elt)^accum in f elt accum (* same effect as above, we did a no-op *)

- Now,

fold_rightjust takes the base case (""here) and the recursion code (fhere) as general parameters:

let rec fold_right f l init =

match l with

| [] -> init (* "" is now the parameter init *)

| elt :: elts ->

let accum = fold_right f elts init in (* same as above but forwarding extra parameters f / init *)

f elt accum (* same code as above but f passed in now as a parameter *)

- Now let’s re-constitute the particular example we had above by passing the base/recursion code back in again:

fold_right (fun elt accum -> (Char.escaped elt)^accum) ['a';'b';'c'] ""

Another example with summating done manually (init case is 0, function is (+) which is fun elt accum -> elt + accum)

let rec summate_right l = match l with

| [] -> 0

| elt :: elts -> (+) elt (summate_right elts)

;;

summate_right [1;2;3];; (* = (1+(2+(3+0))) - observe we start from *right* side, fold_right is fold-starting-from-right *)

And now the same thing using our general fold_right (which is also the same as the library function List.fold_right)

List.fold_right (+) [1;2;3] 0

which is the same as

List.fold_right (fun elt accum -> elt + accum) [1;2;3] 0

if we wrote out the +. Note one parameter is the current element and the other is the accumulation.

- Many recursive functions on lists can be expressed with

List.fold_right: they are simple accumulations over a base case.

let rev l = List.fold_right (fun elt accum -> accum @ [elt]) l [];; (* `accum` is reversed tail, `elt` is current head *)

let map f l = List.fold_right (fun elt accum -> (f elt)::accum) l [];; (* `accum` has f applied to all elts in tail *)

let filter f l = List.fold_right (fun elt accum -> if f elt then elt::accum else accum) l [];;

Folding left

fold_leftaccumulates “on the way down” (we pass down the f computed value), whereasfold_rightaccumulates “on the way up” (the f computes after the recursive call)- Recall the

list_max_auxfunction above which accumulated the maximum element seen. - Lets rename the variables we used before to the

accum/elt/eltsones we use for folding

let rec list_max_aux accum l = (* invariant: accum is the maximal integer seen thus far *)

match l with

| [] -> accum (* we are 100% done, and by the invariant this is the biggest integer seen to its the answer *)

| elt :: elts -> if elt > accum then list_max_aux elt elts else list_max_aux accum elts;;

list_max_aux (Int.min_int) [1;2;3;2;-1];;

Here accum is already a parameter since max needs a seed; lets rewrite this to encapsulate the recursion case as f:

let rec list_max_aux accum l =

match l with

| [] -> accum

| elt :: elts -> let f = fun accum elt -> if elt > accum then elt else accum in

list_max_aux (f accum elt) elts

- This code is a bit different than above because we pushed the condition in, but its the same effect

- Observe that by convention the

accum/eltparameters are in opposite order onffor left folding - We can now make the

falso a parameter, which gives usfold_left:

let rec fold_left f accum l =

match l with

| [] -> accum

| elt :: elts -> fold_left f (f accum elt) elts;;

Again all we did was to pull out f as a parameter, let’s pass it back in to show that:

fold_left (fun accum elt -> if elt > accum then elt else accum) (Int.min_int) [1;2;3;2;-1];;

- Observe how when we get to the bottom of the recursion (empty list) we have the fully final value in

accum - So we just need to return … return … return it all the way to the top without touching it.

For summation we can also use fold_left which is now working from the left side:

List.fold_left (+) 0 [1;2;3];; (* computes ((0 + 1) + 2) + 3); note using library function version List.fold_left here *)

- Notice we get the same answer for left and right fold, because the operator

(+)happens to be commutative and associative((0 + 1) + 2) + 3) ~= (0 + (1 + ( 2 + 3)))

- String concatenation

^is not commutative so we see a difference in left vs right folding there:

fold_left (^) "z" ["a";"b";"c"] ;;

fold_right (^) ["a";"b";"c"] "z" ;;

This also shows how the parameter order is slightly different in the two:

List.fold_left’s type is('acc -> 'a -> 'acc) -> 'acc -> ('a list) -> 'accList.fold_right’s type is('a -> 'acc -> 'acc) -> 'a list -> 'acc -> 'acc

Here are a few more examples of folding left:

let length l = List.fold_left (fun accum elt -> accum + 1) 0 l;; (* adds accum, ignores elt *)

let rev l = List.fold_left (fun accum elt -> elt::accum) [] l;; (* e.g. rev [1;2;3] = (3::(2::(1::[]))) - much faster! *)

- For both of these, assume by induction that

accumhas the accumulated result for all list elements earlier in the list - Consider computing

rev [1;2;3]when we have for example gotten to[3](elt=3) in the recursion - At this point can assume the

accumis[2;1], the result for previous elts we passed. - So, put

3on the front (theelt::accum), and we are done!

Pipeling and composition

- Pipelining is like an assembly line: feed output of one stage into the next stage, in a sequence.

- Example: get the element nth from the end from a list, by first reversing and then getting nth element from front.

First try, which works fine:

let nth_end l n = List.nth (List.rev l) n;;

- But, from the analogy of shell pipes

|, we are “piping” the output ofrevintonthfor some fixed n. - Here is an equivalent way to code that using OCaml pipe notation,

|>

let nth_end l n = l |> List.rev |> (Fun.flip(List.nth) n);;

- All

[1;2] |> List.revin fact does is apply the second argument to the first - very simple! - The type gives it away:

(|>)has type'a -> ('a -> 'b) -> 'b - The

Fun.flipis needed to put the list argument second, not first- it is another interesting higher-order function, with type

('a -> 'b -> 'c) -> ('b -> 'a -> 'c).

- it is another interesting higher-order function, with type

- So, e.g.

(Fun.flip(List.nth) 2)is a function taking a list and returning the 2nd element.Function Composition: functions both in and out

Composition operation g o f from math: take two functions, return their composition

let compose g f = (fun x -> g (f x));;

compose (fun x -> x+3) (fun x -> x*2) 10;;

- The type again tells the whole story:

('a -> 'b) -> ('c -> 'a) -> ('c -> 'b)

Currying

- Names the way multi-argument functions work in OCaml: return a function expecting next parameter

- Logician Haskell Curry originally came up with the idea in the 1930’s

- First lets recall how multi-argument functions in OCaml are Curried

let add_c x y = x + y;; (* recall type is int -> int -> int which is int -> (int -> int) *)

add_c 1 2;; (* recall this is the same as '(add_c 1) 2' *)

let tmp = add_c 1 in tmp 2;; (* the partial application of arguments - tmp is a function *)

(* An equivalent way to define `add_c`, clarifying what the above means *)

let add_c = fun x -> (fun y -> x + y);;

Here is the non-Curried version: use a pair of arguments instead

let add_nc (x,y) = x + y;; (* type is int * int -> int - no way to partially apply *)

- Notice how the type of

add_ncdiffers fromadd_c:int * int -> intvsint -> int -> int. - Fact: these two approaches to defining a 2-argument function are isomorphic:

'a * 'b -> 'c~='a -> 'b -> 'c - (This isomorphism also holds in set theory, you may have already seen it)

To “prove” this we make functions (on functions) to convert from one form to the other

curry- takes in non-curry’ing 2-arg function and returns a curry’ing versionuncurry- takes in curry’ing 2-arg function and returns an non-curry’ing version

Since we can then go back and forth between the two representations, they are isomorphic.

let curry fnc = fun x -> fun y -> fnc (x, y);;

let uncurry fc = fun (x, y) -> fc x y;;

let new_add_nc = uncurry add_c;;

new_add_nc (2,3);;

let new_add_c = curry add_nc;;

new_add_c 2 3;;

Observe the types themselves pretty much specify their behavior

curry : ('a * 'b -> 'c) -> ('a -> 'b -> 'c)

uncurry : ('a -> 'b -> 'c) -> ('a * 'b -> 'c)

let noop1 = curry (uncurry add_c);; (* a no-op *)

let noop2 = uncurry (curry add_nc);; (* another no-op; noop1 & noop2 together show isomorphism *)

Misc OCaml

See module Stdlib for various functions available in the OCaml top-level like +, ^ (string append), print_int (print an integer), etc.

See the Standard Library for modules of functions for Lists, Strings, Integers, as well as Sets, Maps, etc, etc.

print_string ("hi\n");;

Some Stdlib built-in exception generating functions (more on exceptions later)

(failwith "BOOM!") + 3 ;;

Invalid argument exception invalid_arg:

let f x = if x <= 0 then invalid_arg "Let's be positive, please!" else x + 1;;

f (-5);;

Type abbreviations are possible via keyword type

type intpair = int * int;;

let f (p : intpair) : int = match p with

(l, r) -> l + r

;;

(2,3);; (* ocaml doesn't call this an intpair by default *)

f (2, 3);; (* still, can pass it to the function expecting an intpair *)

((2,3):intpair);; (* can also explicitly tag data with its type *)

Variants

We saw a simple examples of variants earlier in the option type; now we go into the full possibilities

- Related to

uniontypes in C orenums in Java: “this OR that OR theother” - Like lists/tuples they are immutable data structures

- Each case of the union is identified by a name called a constructor which serves for both

- constructing values of the variant type

- destructing them by pattern matching

Example of how to declare a new variant type for doing mixed arithmetic (integers and floats)

type mynumber = Fixed of int | Floating of float;; (* read "|" as "or" *)

Fixed(5);; (* tag 5 as a Fixed *)

Fixed 5;; (* parens optional as is often the case in OCaml *)

Floating 4.0;; (* tag 4.0 as a Floating *)

- Constructors must start with Capital Letter to distinguish from variables (

FixedandFloatinghere) - The

ofindicates what type of thing is under the wrapper, leave outofand there will be nothing - Type declarations are required but once they are in place type inference on them works

- Note constructors look like functions but they are not – you always need to give the argument

Destruct variants by pattern matching like we did for Some/None option type values:

let ff_as_int x =

match x with

| Fixed n -> n

| Floating z -> int_of_float z;;

ff_as_int (Fixed 5);; (* beware that ff_as_int Fixed(5) won't parse properly!! Super commmon error!

ff_as_int @@ Fixed 5 will though *)

An example using the above variant

let add_num n1 n2 =

match n1, n2 with (* note use of pair here to parallel-match on two variables *)

| Fixed i1, Fixed i2 -> Fixed (i1 + i2)

| Fixed i1, Floating f2 -> Floating(float i1 +. f2) (* need to coerce with `float` function *)

| Floating f1, Fixed i2 -> Floating(f1 +. float i2) (* ditto *)

| Floating f1, Floating f2 -> Floating(f1 +. f2)

;;

add_num (Fixed 10) (Floating 3.14159);;

Multiple data items in a single variant case? Can use tuple types

type complex = CZero | Nonzero of float * float;;

let com = Nonzero(3.2,11.2);;

let zer = CZero;; (* example of a variant without a payload *)

Recursive data structures

- An important use of variant types

- Functional programming is highly suited for computing over tree-structured data

- Recursive types can refer to themselves in their own definition

-

Similar in spirit to how C structs can be recursive (but, no pointer needed here)

- Warm-up: homebrew lists - built-in list type is not in fact needed

Mtrepresents[],Cons(hd,tl)representshd::tl

type 'a mylist = Mt | Cons of 'a * ('a mylist);;

let mylisteg = Cons(3,Cons(5,Cons(7,Mt)));; (* equivalent in spirit to [3;5;7] *)

- First notice that we can refer to

mylistin its own type definition: its a recursive type - Also observe how above type takes a (prefix) argument,

'a–mylistis a type function,'ais the type of list elements -

Perhaps better syntax would have been

type mylist(t) = Mt | Cons of t * (mylist(t)) - Coding is analogous with built-in lists but without special sugar to make lists like

[1;2;3] -

Lets write

mapas a test to show how easy it islet rec map ml f = match ml with | Mt -> Mt | Cons(hd,tl) -> Cons(f hd,map tl f);; let map_eg = map mylisteg (fun x -> x - 1);;

OCaml Lecture V

Trees

- Binary trees are like lists but with two self-referential sub-structures not one

- Here is one tree definition; note the data is (only) in the nodes here

- … n-ary trees are a direct generalization of this pattern

type 'a btree = Leaf | Node of 'a * 'a btree * 'a btree;;

Example trees

let whack = Node("whack!",Leaf, Leaf);;

let bt = Node("fiddly ",

Node("backer ",

Leaf,

Node("crack ",

Leaf,

Leaf)),

whack);;

(* Type error; like lists, tree data must have uniform type: *)

(* Node("fiddly",Node(0,Leaf,Leaf),Leaf);; *)

Functions on binary trees are similar to functions on lists: use recursion

let rec add_gobble binstringtree =

match binstringtree with

| Leaf -> Leaf

| Node(y, left, right) ->

Node(y^"gobble",add_gobble left,add_gobble right)

;;

- Remember, as with lists this is not mutating the tree, its building a “new” one

-

Also as with

List.mapearlier we could write atree_mapfunction over trees since this is the common pattern of “make a new tree by applying some functionfto each element of the tree” (we won’t in fact but it would be a good exercise) - Recall a binary search tree is a binary tree where all values in any left subtree are smaller (or equal to) any value in the node itself or in any right subtree

- Let us now write a binary search tree

lookupfunction - Invariant: input tree is a binary search tree (bst) with the above property

let rec lookup x bst =

match bst with

| Leaf -> false

| Node (y, left, right) ->

if x = y then true else if x < y then lookup x left else lookup x right

;;

lookup "whack!" bt;;

lookup "flack" bt;;

Let us now define how to insert an element but to still preserve the bst property.

let rec insert x bst =

match bst with

| Leaf -> Node(x, Leaf, Leaf)

| Node(y, left, right) ->

if x <= y then Node(y, insert x left, right)

else Node(y, left, insert x right)

;;

- This is also not mutating – it returns a whole new tree - !

- (well, not exactly, we can share subtrees with old tree; more below)

- If you then want to insert another element you need to pass the result from the previous call.

let bt2 = insert "goober " bt;;

bt;; (* observe bt did not change after the insert *)

let bt3 = insert "slacker " bt2;; (* pass in bt2 to accumulate both additions in bt3 *)

let manyt = List.fold_left (Fun.flip insert) Leaf

["one";"two";"three";"four";"five";"six";"seven";"eight";"nine"]

(* folding for serial insert; accum here is the tree so keep passing it along *)

- You have already been programming with immutable data structures –

lists - For trees you are used to mutating to insert, delete, etc so takes some getting used to

- It looks really inefficient since an insertion is making a “totally new tree”

- but, the compiler can in fact share all subtrees along the spine to the new node - “only” log n cost

- referential transparency at work!

End Core OCaml used in the course

- The assignments mainly use what we covered above

- We will now quickly cover a few more OCaml features which we will rarely use

- Note that the toy languages we study will mirror OCaml to some degree so we at least want a basic understanding of OCaml’s records, state, and exceptions

- FbR will be our Fb records extension, FbS for state, and FbX for eXceptions.

Records

- Like tuples but with labels on fields.

- Similar to the

structs of C/C++. - The types must be declared with

type, just like OCaml variants. - Also like variants and tuples they can be used in pattern matches.

- Also also record fields are immutable by default, so not like Python/Javascript dictionaries/objects

Example: a declaring record type to represent rational numbers

type ratio = {num: int; denom: int};;

let q = {num = 53; denom = 6};;

Destructing records via pattern matching:

let rattoint r =

match r with

{num = n; denom = d} -> n / d;;

Only one pattern matched so can again inline pattern in function’s/let’s

let rat_to_int {num = n; denom = d} = n / d;;

Equivalently could use standard method of dot projections, but happy path in OCaml is patterns

let unhappy_rat_to_int r =

r.num / r.denom;;

One more example function with records

let unhappy_add_ratio r1 r2 = (* Doesn't use patterns, boo hoo *)

{num = r1.num * r2.denom + r2.num * r1.denom;

denom = r1.denom * r2.denom};;

unhappy_add_ratio {num = 1; denom = 3} {num = 2; denom = 5};;

let happy_add_ratio {num = n1; denom = d1} {num = n2; denom = d2} =

{num = n1 * d2 + n2 * d1; denom = d1 * d2};;

End of Pure Functional programming in OCaml

- On to side effects

- But before heading there, remember to stay OUT of side effects unless really needed - that is the happy path in OCaml coding

- The autograder may let you get away with side effects on assignment 1/2 but you will get a manual ding by the CAs.

State

- Variables in OCaml are never directly mutable themselves; only (indirectly) mutable if they hold a

- reference

- mutable record

- array

Indirect mutability - variable itself can’t change, but what it points to can.

- C language perspective on this: if

pis anint *type (pointer),*p = 5;is what you can do in OCaml – change what pointer points top = someotherpointeris what you can’t do, changing the pointer itself.

- items are immutable unless their mutability is explicitly declared

Mutable References

- References are more like standard PL variables which can change but there are some subtle differences

- You can’t make a reference without any value in it, there is no

nullpointer possible. - You need to explicitly dereference them so they are like

int *types in C mentioned above - References are an immutable pointer to a mutable block, can change the pointed-to but not the pointer.

- You can’t make a reference without any value in it, there is no

let x = ref 4;; (* must declare initial value when creating; type is `int ref` here *)

Meaning of the above: x refers to a fixed cell. The contents of that fixed call can change, but not x.

(* x + 1;; *) (* a type error, need to explicitly dereference *)

!x + 1;; (* need `!x` to get out the value; parallels `*x` in C *)

x := 6;; (* assignment is := not =. x must be a ref cell. Returns unit, () - goal is side effect *)

!x;; (* Mutation happened to contents of cell x *)

let x_alias = x;; (* make another name for x since we are about to shadow it *)

let x = ref "hi";; (* does NOT mutate x above, instead another shadowing definition *)

!x_alias;; (* confirms the previous line was not a mutation, just a shadowing *)

Refs are “really” mutable records

'a refis in fact implemented by an OCaml mutable record which has one field namedcontents:'a refabbreviates the type{ mutable contents: 'a }- The keyword

mutableon a record field means it can be mutated

let x = { contents = 4};; (* identical to `let x = ref 4` *)

x := 6;;

x.contents <- 7;; (* same effect as previous line: backarrow mutates a field *)

!x + 1;;

x.contents + 1;; (* same effect as previous line *)

Declaring your own mutable record: put mutable qualifier on field

type mutable_point = { mutable x: float; mutable y: float };;

let translate p dx dy =

p.x <- (p.x +. dx); (* observe use of ";" here to sequence effects *)

p.y <- (p.y +. dy) (* ";" is useless without side effects (think about it) *)

;;

let mypoint = { x = 0.0; y = 0.0 };;

translate mypoint 1.0 2.0;;

mypoint;;

Observe: mypoint is immutable at the top level but it has two spots x/y in it where we can mutate

Arrays

- Fairly self-explanatory, we will just flash over this

- Arrays are lists but we

- can mutate elements

- can quickly (constant time) access the n-th element

- but are hard to extend or shorten

- The main annoyance is the syntax is non-standard since

[..]is already used for lists - Have to be initialized before using

- in general there is no such thing as “uninitialized”/”null” in OCaml

let arr = [| 4; 3; 2 |];; (* one way to make a new array, or `Array.make 3 0` *)

arr.(0);; (* access notation *)

arr.(0) <- 5;; (* update notation *)

arr;;

Exceptions

- OCaml has a standard (e.g. Java-like) notion of exceptions

- Unfortunately types do not include what exceptions a function will raise - an outdated aspect of OCaml.

- If a side effect is notated in the type that is called an effect type - e.g. Rust uses this for mutation effects

- Modern OCaml coding style is to minimize the use of exceptions

- Causes action-at-a-distance, hard to debug

- Instead follow the old C approach of bubbling up error codes:

- return

Some/Noneand make the caller explicitly handle theNone(error) case. - we covered this a bit with the

nice_divexample above.

- return

There are a few built-in exceptions we used previously:

failwith "Oops";; (* Generic code failure - exception is a built-in `Failure` exception *)

invalid_arg "This function works on non-empty lists only";; (* Invalid_argument exception *)

Here is a simple example of how to declare and use exceptions in OCaml

exception Bad of string;; (* Declare a new exception named `Bad` with a string payload *)

let f _ = raise (Bad "keyboard on fire");;

(* f ();; *) (* raises the exception to the top level *)

(* (f ()) + 1;; *) (* recall that exceptions blow away the context *)

let g () =

try

f ()

with (* `catch` is the analogous keyword in Java; use pattern matching in handlers *)

Bad s -> Printf.printf "exception Bad raised with payload \"%s\" \n" s

;;

g ();;

Modules

Background on modules in programming languages

- a module is a larger level of program abstraction, think functional components or library.

- e.g. Java package, Python module, C directory, etc

- something is needed for all but very small programs: imagine a file system without directories/folders as an analogy to a PL without modules

- We are not going to study the theory of modules later in the course so will cover some of the principles now

General principles of modules

- Modules have names they can be referenced by

- A module is a container of code: functions, classes, types, etc.

- Modules can be file-based: one module per file, module name is file name. Or, directory-based. Or, neither.

- The module needs a way to

- import things (e.g. other modules) from the outside;

- export some (or all) things it has declared for outsiders to use;

- A module may hide some things for internal use only

- allows module users to avoid seeing grubby internals - a higher level of abstraction

- avoids users mucking with internals and messing things up

- Separate name spaces, so e.g. the

Window’sreset()won’t clash

with aFile’sreset(): useWindow.reset()andFile.reset() - Nested name spaces for ever larger software:

Window.Init.reset() - In compiled languages, modules can generally be compiled separately (only recompile the changed module(s))

- speeds up incremental recompilation, an important feature in practice.

Modules in OCaml

- We already saw OCaml modules in action

- Example:

List.mapis an invocation of the map function in the built-inListmodule. - Modules always start with a Capital letter, just like variant labels.

- Example:

- We now study how we can build and use our own OCaml modules

- We focus here on building modules via files; there are other methods in OCaml which we skip

- The FbDK you will use for writing interpreters and typecheckers uses modules so it will help to understand whats going on with it

Making a module

- Assignment 1/2 require you to fill out a file

assignment.ml - This is in fact creating a module

Assignment(notice the first letter (only) is capped) dune utopwill compile your module and load it in the top loop- You then can type

Assignment.doit 5;;etc to access the functions in the module’s namespace - Or, use

open Assignment;;to make all the functions in the module available at the top level.

Separate Compilation with OCaml

- File-based modules such as

assignment.mlare compiled separately. - This is the traditional

javac/cc/etc style of coding, and is done with done withocamlcin ocaml - Also in the Java/C spirit, it is how you write a standalone app in OCaml

- The underlying

ocamlccompiler you don’t need to directly invoke, in this course we will give youdunebuild files which invoke the compiler for youduneismakefor OCamldune buildinvokes the OCaml compiler on all the files in a project- if you are curious what actual compiler calls are happening, add

--verboseto the build command dune testwill build and then run any tests

An example of a separately-compiled OCaml program

- See set-example.zip for the example we cover in lecture.

- The file

src/simple_set.mlis the set data structure and will compile to moduleSimple_set. - Observe how a module can also contain type definitions, this is a key differece of OCaml

Using the Simple_set library module

dune testwill run some simple tests intests/tests.ml- We can use

dune utopto load the library module into a freshutop, after which we can play with it

Simple_set.emptyset;; (* simple_set.ml's binary is loaded as module Simple_set *)

open Simple_set;; (* open makes `emptyset` etc in module available without typing `Simple_set.` *)

let aset = List.fold_left (Fun.flip add) emptyset [1;2;3;4] ;;

contains 3 aset ;;

Running a command-line executable

Set_mainis another module here, in filesrc/set_main.ml.- The

dunefile declares that module to be an executable, it will make a runnable binary out of it - After

dune build, typing_build/default/src/set_main.exeto shell will invoke the binary - It expects a search word and a file and will look for that string in the file

- e.g. try

_build/default/src/set_main.exe dune dune-project

- e.g. try

For the interpreters and typecheckers you write, you will be able to run them with dune utop or as an executable.

End of OCaml!

- If you want to learn more about software engineering in OCaml, take Functional Progamming in Software Engineering in the fall